This is continuation of part series post of Virtual Memory - Part 1, Virtual Memory - Part 2

Table of Contents

Address Space

The box in the picture above represents 32-bit address space, i.e., 4GB of memory. If this would be a 64-bit address space, then there would be a large gap between the end of kernel space and beginning of userspace as we don’t use all of the 64-bit address space yet.

Address space is divided into two parts. The first part is dedicated to the kernel, and the second part is dedicated to the user. When the context switching happens, we switch only the user part of the virtual memory. When the system is booted, the kernel part of the virtual memory is loaded and it just always sits there. At any given time, only one process is runnable so during context switch we logically take the context of userspace part of virtual memory and keep it aside and load the state of a new process using MMU.

Kernel user space is allocated based on available physical memory, but generally kernel space doesn’t take more than one-third of the memory or max of 2 GB of memory. It is suitable for the kernel part of virtual memory to take more space for some use cases. For example, for multiple small applications like running web service with many apache servers, they do not need a lot of user space in virtual memory, in fact, it would be better off kernel section gets more space in virtual memory so that kernel can do lot more caching, application which needs lot of networking, disk I/O or kernel intensive activity benefit by kernel having more space.

Many times in modern computers we have memory more than 4 GB for the 32-bit system. Even though we have 8 GB memory but for 32-bit system, only 4 GB is addressable at a time. So rest of the memory is used for storing the unloaded user processes which are not part of the action as of now. All in all, extra space is used as a kind of cache}.

Kernel space of virtual address is made such that it is not visible to user space of virtual memory. Kernel space is mapped neither readable not writable. The reason for not making Kernel space as not readable as a lot of privileged information resides in kernel space such as passwords. On the other hand, the kernel can read the contents of the user process. If the user process wants to read some data, then we add data to kernel buffer then we just do the memory to memory copy to the location where the user has asked to have it placed in. This way, data is transferred quickly and efficiently.

As the user process runs in virtual address space kernel does not. The kernel is hard-wired, and all part of the kernel is in physical memory. If the kernel has a gigabyte of address space doesn’t mean kernel starts with using a gigabyte of address space, we load just the first part of kernel in memory at the time of boot up. All the initialized data is put right into the memory, and the uninitialized data area is allocated and zeroed. Then some preliminary kernel data structure is allocated. From there on kernel would simply malloc() additional things it needs. When kernel decides to free up its memory, then it frees up the pages, and the pages are added to the free list of the pages.

The user process is all paged. Historically text was used to start at address 0. Problem with text starting with address 0 is that if you have null pointer and now you are trying to read from the small offset from the null pointer then all you get is data from text of the program which was not intended. So the text address is moved up a page or two.

After text is uninitialized and initialized data. Heap starts after initialized data section and move upwards. Heap can grow up to user stack. Starting from the top of user process space just below the kernel are the argument vector, and environment vector would be placed, and from there, user stack grows down. In theory heap and stack grows towards each other but administratively we put limit sizes on how much stack and heap can grow. Generally on stack order of limit put is ~4MB. When the stack grows beyond a limit, it results in fault. If a user wants to grow the limit of the stack, i.e., the stack can grow more using setr system call. The reason stack limit is small is that typical applications do not use a lot of stack space. Most of all, the applications put the majority of data on the heap. The Another reason is the class of errors due to infinite recursion in the stack is catastrophic. When a stack is allowed to grow up to large memory and in case of infinite recursion of the stack; we would end up using all the memory leading to multiple page fault and later when we use all the space would end up into huge core dump which will further end up using a huge amount of disk space.

Heap is given a gigabyte of space limit. These days lot of application runs using shared libraries. Before even the program starts, we have to load the shared libraries. During the boot-up phase, some of the critical shared libraries which are required for basic operations like system calls are mapped to the user space by the kernel using mmap. mmap system call allows the kernel to specify wherein the memory location to map the data. All the libraries are compiled using the position-independent code. The algorithm used by mmap is to look at the administrative limits of the stack and place the shared libraries just below the administrative limits. The philosophy here is that stack cannot grow beyond administrative limits else it leads to a fault so a page or two below we place the shared libraries.

Problem Applications runs into the problem when they try to grow the size of stack beyond the administrative limits when shared libraries have already been located below stack administrative limits, and now growing stack would lead to conflict with shared libraries.

Solution To deal with a problem of the bigger stack is to let parent figure out when they are starting the process, they start by the bigger stack, i.e., Terminal (parent) forks the application, and initially, we have two copies, one parent and one child. The child would do an exact overlay of the same copy of a parent with a new thing we want to run. So before we do the exec parent observing application would increase the stack limit by setr system call and then exec the process so that we have a bigger stack and then shared libraries are mapped. The problem sometimes could be a parent does not know that the application needs the bigger stack.

Another approach here is that application can use setr system call which would grow the stack but can overlap with shared libraries but then the application needs to exec itself again so that it throws away the previous allocation and start fresh allocation with an all-new bigger stack.

Virtual Memory Design Considerations

Overall we are going to look at processes are made up of regions. The region is just a piece of address space being treated in a common way for example when the program starts the text part of the address space you treat as read-only demand page from file and initialized data is being treated as copy on-demand page from file and uninitialized data area is zero fill on demand. So different space in address space is being treated in different ways. Historically these regions are sometimes called segments.

Shared Memory

Earlier interprocess communication was done using pipes or sockets where one application writes the data at one end, and another process reads the data from another end. Problem with this was system call needs to be invoked, and then the data needs to be copied from one address space to another. The idea of shared memory was to create a part of address space or region of address space in which same memory is mapped to these processes. One process can write into this region of address space, and another process can read from this address space region. Using this approach system call and copying data from kernel space to user space can be avoided. Given two processes are accessing the same address region co-ordination is needed, so we use semaphores are used. Pipes are suitable inter-process communication mechanism when sharing a large amount of data.

File Mapping

In case of accessing files rather than performing I/O to and fro to disk, we map the region of a file into memory. We manipulate the part we need and write back. The whole files do not need to be a map at once and can be mapped in parts when required. mmap can be used to map file from starting offset to the number of bytes into memory. The file mapping can be done in shared memory or private memory. Private memory is the region where modification made to the file is only visible to the process not to other processes in the system whereas in shared memory case another process would have visibility of changes made to the file. Other processes in private mapping would see the pristine copy of the file in the memory. At the time of process exit, the changes made to private memory would be discarded and would not be written back to the file on disk. This is particularly useful in case of initializing data in executables, which is put in address space as private mapping. As we don’t want one process executing ls command would show the same output/data to another process.

Device Memory Mapping

This is for any device which looks like memory; an example of this is frame buffer. With frame buffer, we have pixel layout for the screen in an array of the word, so when we change a particular word in memory, i.e., changing brightness or some setting for pixel on the screen. We can change these values by reading and writing using system calls, but that would lead to poor performance. It is more efficient to map the device into memory so that data modifications can be done at high speed.

Copy On Write Over Fork

When we fork we create an exact copy of parent but much more the common thing is to create the same copy of the program, i.e., the shell forks another copy of shell it then does exact of the thing where it throws away the copy of the shell and overlays with executable we want to run. It is much work to create a copy, so instead, we create a copy of the page table. We create a copy of parent page table entry both processes are referring to the same page table entries. We don’t want parent and child to see the changes of each other, so we mark all the entries as read-only.

In the case of vfork, we take a page table of the parent and give that page table to the child until child exec, and then we give the page table back to the parent. Problem with vfork is that changes what the child makes with the parent’s page table would be evident in the parent. If the child ends up changing many stack entries and then the parent comes back, it would be devastating.

Sparse Address Space

- Multi-level pages tables

- Allocation of Swap Space

- Limits on virtual memory

- Machine independence

API’s

- mmap

- msync - Allow much finer grain control over the flushing of CPU caches.

- fsync - Selective sync of files. So if part of the file is modified in memory then using fsync, only selective parts can be synced to disk.

- msync - For databases which have tons of data to be synced but not the whole database to be sync to disk on each change, msync can be used.

- mprotect - Protect part of the address space, i.e., make a part of address space read-only.

- madvice - Advice kernel how page table is going to be used, i.e., sequential access, read ahead and write-behind or random.

- mlock - Real-time process cannot afford a delay of page fault, so mlock allows the range of address space to be locked and brought to the memory all at once hence avoiding chances of any page fault. For databases, mlock can be used to pin pages in the memory until ready to commit them.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

void *addr = mmap(

void *addr, /* base address */

size_t len, /* length of region */

int prot, /* protection of region */

int flags, /* mapping flags */

int fd, /* file to map */

off_t offset); /* offset to begin mapping */

);

mprotect(const void *address, int length, int protection);

mlock(const void *address, size_t length);

msync(void *address, int length, int flags);

Virtual Memory Data Structures

Address space

- Collection of objects. Each object is backing some parts/regions of the address space.

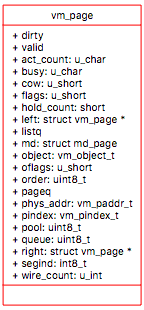

- Each object have to keep track of what pages it has resident, i.e., which part of the object is around.

- Keep track of physical page which it belongs to. The page may be mapped to different processes, but any given page is mapped to exactly one virtual page of one object. Page belongs to an object, and it’s a particular part of an object even it is mapped to different processes, it’s still got a single identity. We would not be tracking which processes are referencing it but rather what is its content it belongs to.

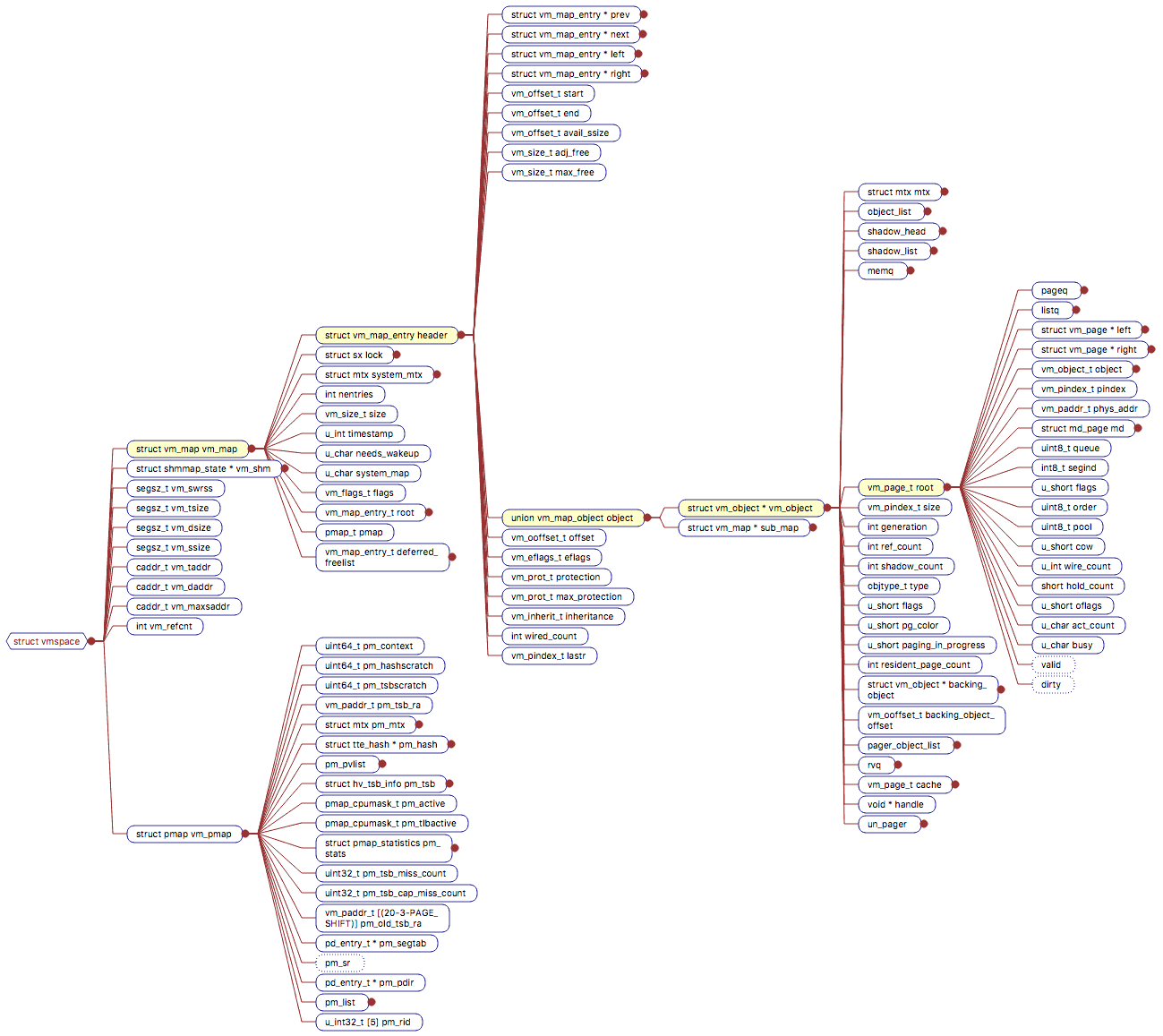

Big Picture

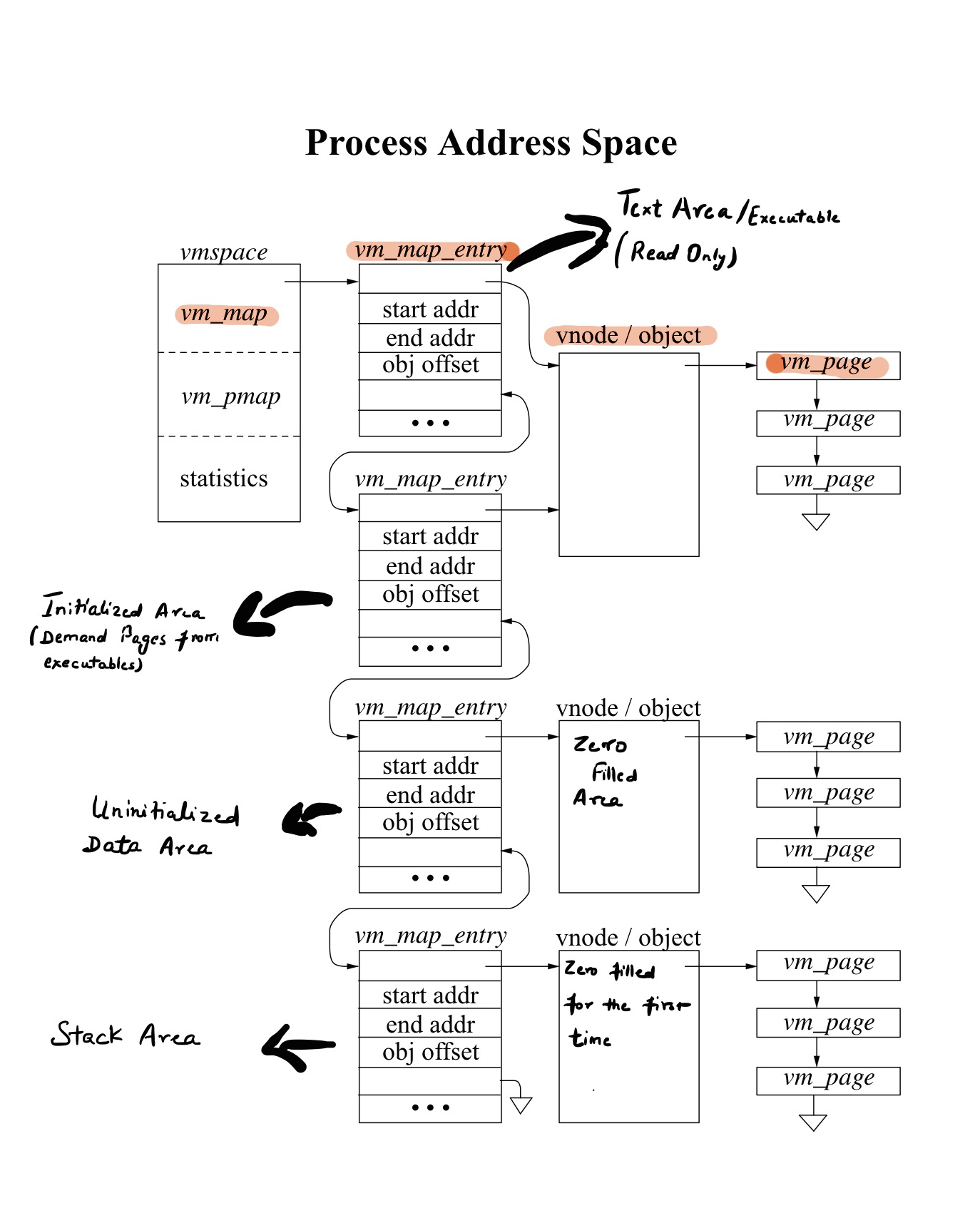

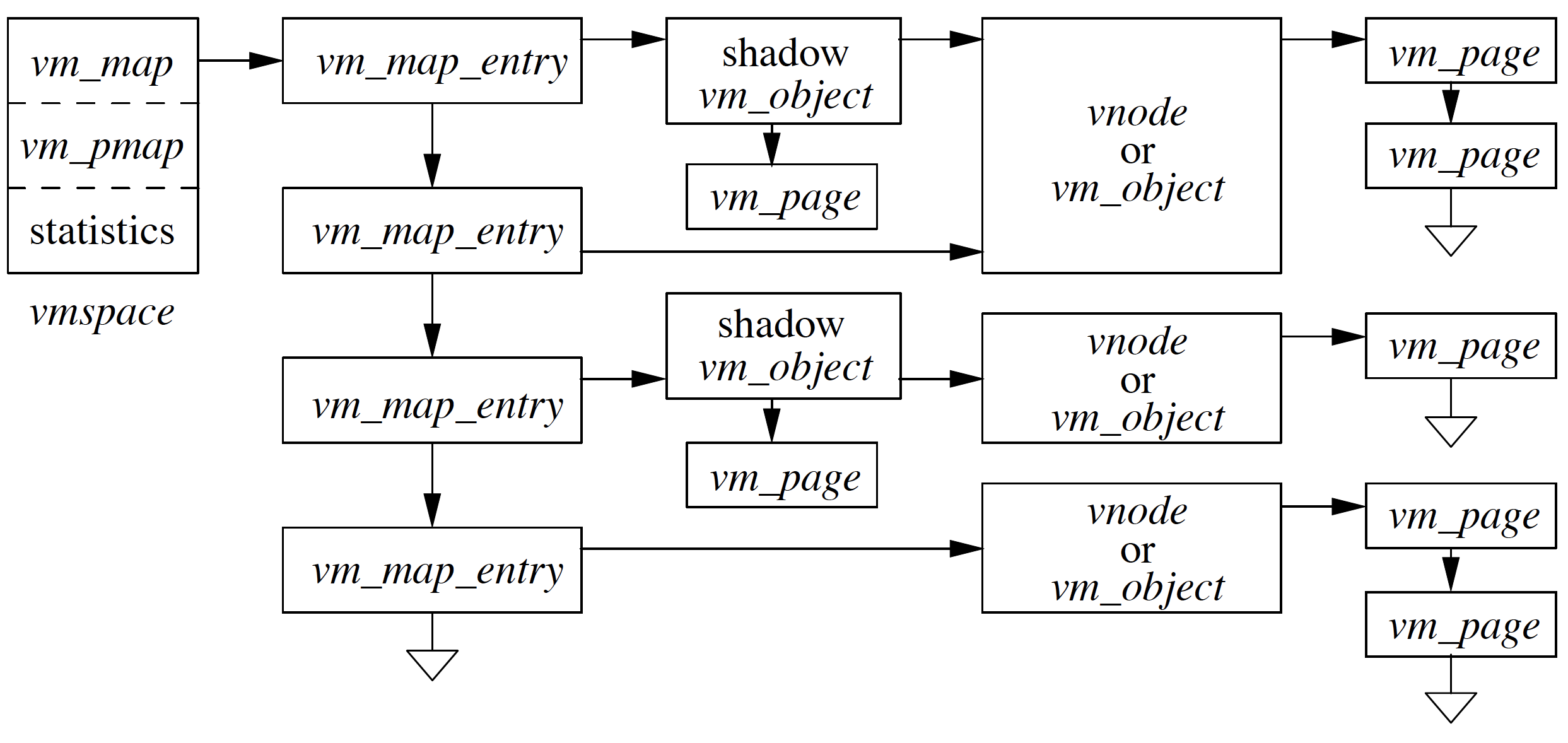

Process starts executing and immediately after it is loaded into the memory, we have four vm_map_entry blocks. First vm_map_entry component is for Text, the second component is for Initialized data, third is for Uninitialized data, and the last component is for Stack. We don’t have any shared libraries mapped here yet. All of the data structure above is a machine-independent data structure with two exceptions. First one being vm_pmap member of vmspace, which is physical map is machine dependent. It is the physical table hardware which is used to translate from virtual to physical memory. The second one is vm_page, which has a little bit of structure in it, which is machine-dependent.

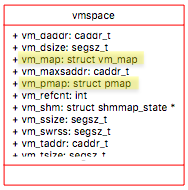

vmspace

vmspace describes the structure of address space as whole. vmspace is broken into three parts:

- vm_map - Machine independent stuff

- vm_pmap - Machine dependent stuff

- statistics - Virtual memory related stats

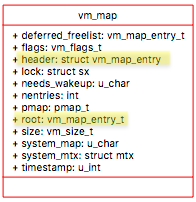

vm_map

vm_map is made up of vm_map_entry and each vm_map_entry describes a region of the address space. Each region has a start and end address. Each of these address describes what part of address space it is representing.

As described before figure represents the address when process just came to life, so we don’t have vm_map_entry for a shared library but for other parts of memory like text area, initialize, uninitialized area and stack area. Later, when we come to the point where shared libraries need to be mapped, we created another vm_map_entry specifically for shared libraries. Each vm_map_entry have range of addresses it covers.

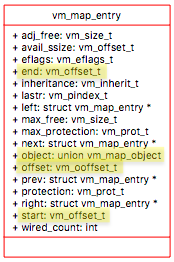

vm_map_entry

Each vm_map_entry have object address union vm_map_object and the offset of type vm_offset_t which is the information about where in object the particular vm_map_entry is referencing.

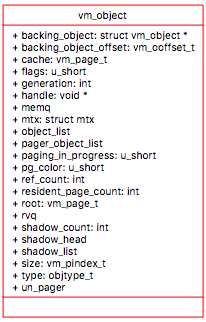

vm_object

vm_object The first vnode/object represents the executable file. The starting address is text and initialized data at the very end section in vnode.

For things like uninitialized data area, heap and the stack the vnode object are called anonymous objects. Anonymous objects are unlike other objects where the file is backing it and creates itself.

Data Members - vmspace

Page Faults and VM Data Structures

Program is running along, and now it hits some address which MMU kicks out, and reason of kicking out is either the address is out of range of address space, or it hits the non-resident page. When running, we don’t know which case we have hit here, and all we know is the virtual address that needs to be served. First, we need to determine, if the address is valid for the process. To validate that we walk through each vm_map_entry and validate if address falls between start and end addresses of vm_map_entry region. If the address doesn’t fall in any address ranges, then we hit segment fault.

Let’s say the address falls into the second vm_map_entry which is for initialized data area in Figure AddressSpace, then the address belongs to some part of initialized data (in vnode). In order to go to vnode vm_object to get that page we need to know where in the initialized area(in vnode) is an exactly logical page that we want.

In vnode vm_object we want to know which page it maps to. If page is not present in list of pages which are pointed by vnode vm_object then it is responsibility of vm_object to allocate a new page get it filled either with file or get it zero etc. depending on kind of object vm_object it is. vm_object then put that new page into it’s list and in the end return the pointer to that page.

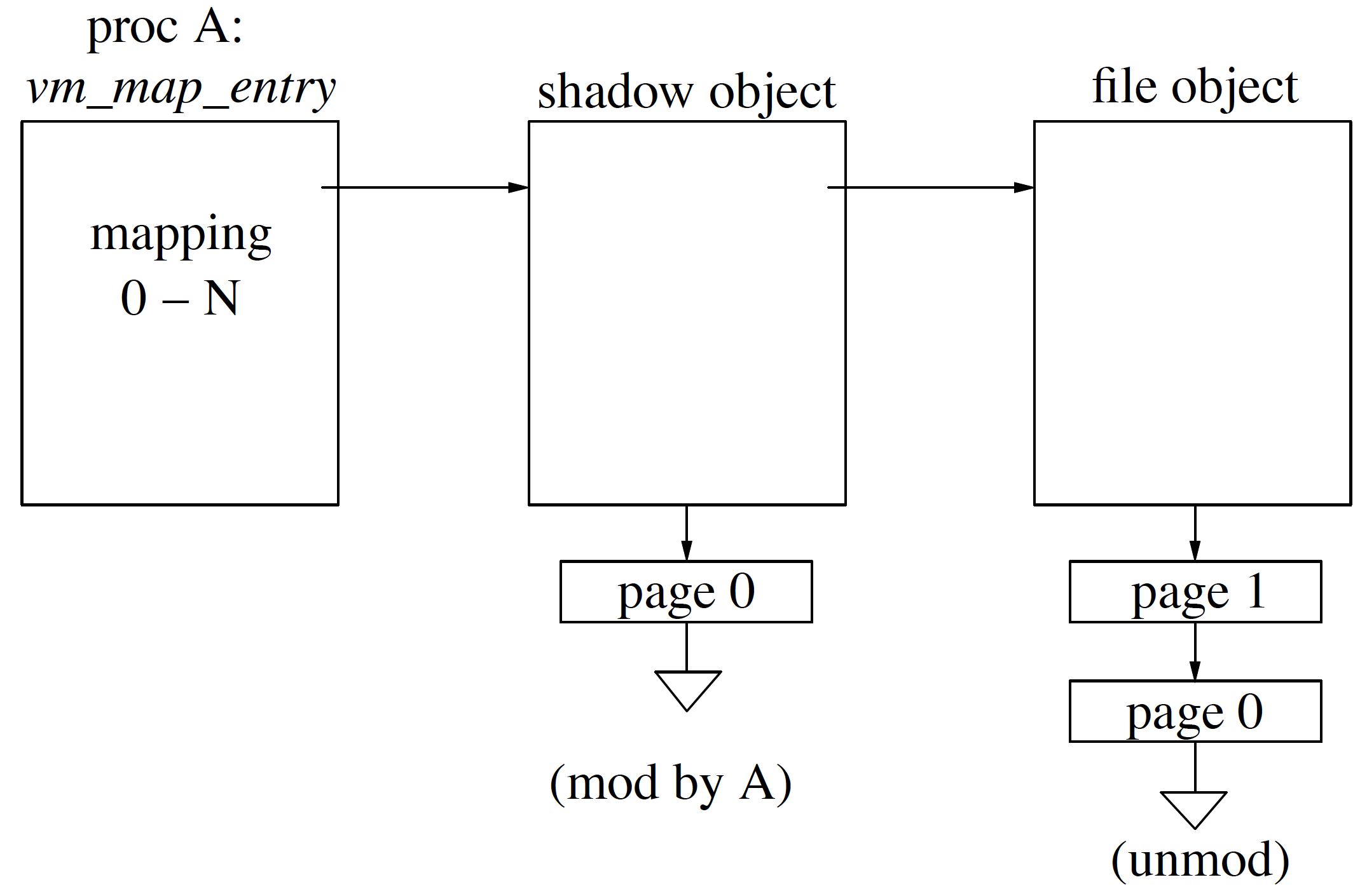

Problem In the above example, we had a page fault for initialized data region, and we brought the new page and mapped to vm_object, which eventually is part of vmspace. Given initialized data is supposed to be private mapping but in this case, we have mapped the page to vmspace, so any changes in page would reflect everywhere. Solution We need a mechanism where we associate a copy of a page instead of the original page. The mechanism is called shadow object.

As shown in Figure instead of mapping page from vm_object we allocate new vm_object i.e. shadow object and then copy the data to shadow object which then maps to vmspace.

Shadow Objects

As we see in Figure shadowobjectsoverview, on the left we see map entry and on the right is underlying object and in the middle is shadow object. When a page fault occurs in map entry we are going to walk down in hierarchy from left to right to determine if the required page is present. So, if page 0 faults then we look into shadow objects if not found in shadow objects then we go to underlying object and if not found in the underlying object then the page is swapped and a new page is brought, a new object is created.

If process A has faulted page 0 and if A faulted page 0 to only read (not write) it then we could give it the pointer to the unmodified copy of underlying object with read-only bit set. In case, page 0 faulted for modification then we need to allocate the shadow object, copy the original contents from underlying object to newly allocated shadow object, map the shadow object for modification and in the end present the shadow object map entry. When the process exits, the shadow objects would be flushed, shadow object looks a lot like anonymous object as in the changes has to be written back to swap area in case of modification before exit.

Shadow objects are not zero-filled instead the contents are copied from underlying object when they are newly created. When short of memory we don’t want to create another shadow object, so instead of creating the shadow object, we pick the page entry from underlying object and just move it over to shadow object. The underlying object lost it’s a copy of the page; instead, it now belongs to shadow object. In case another process now asks for the same page, we would have to go and fetch the page from main memory or disk. This strategy is generally used when the system is left with less than 5% of memory.

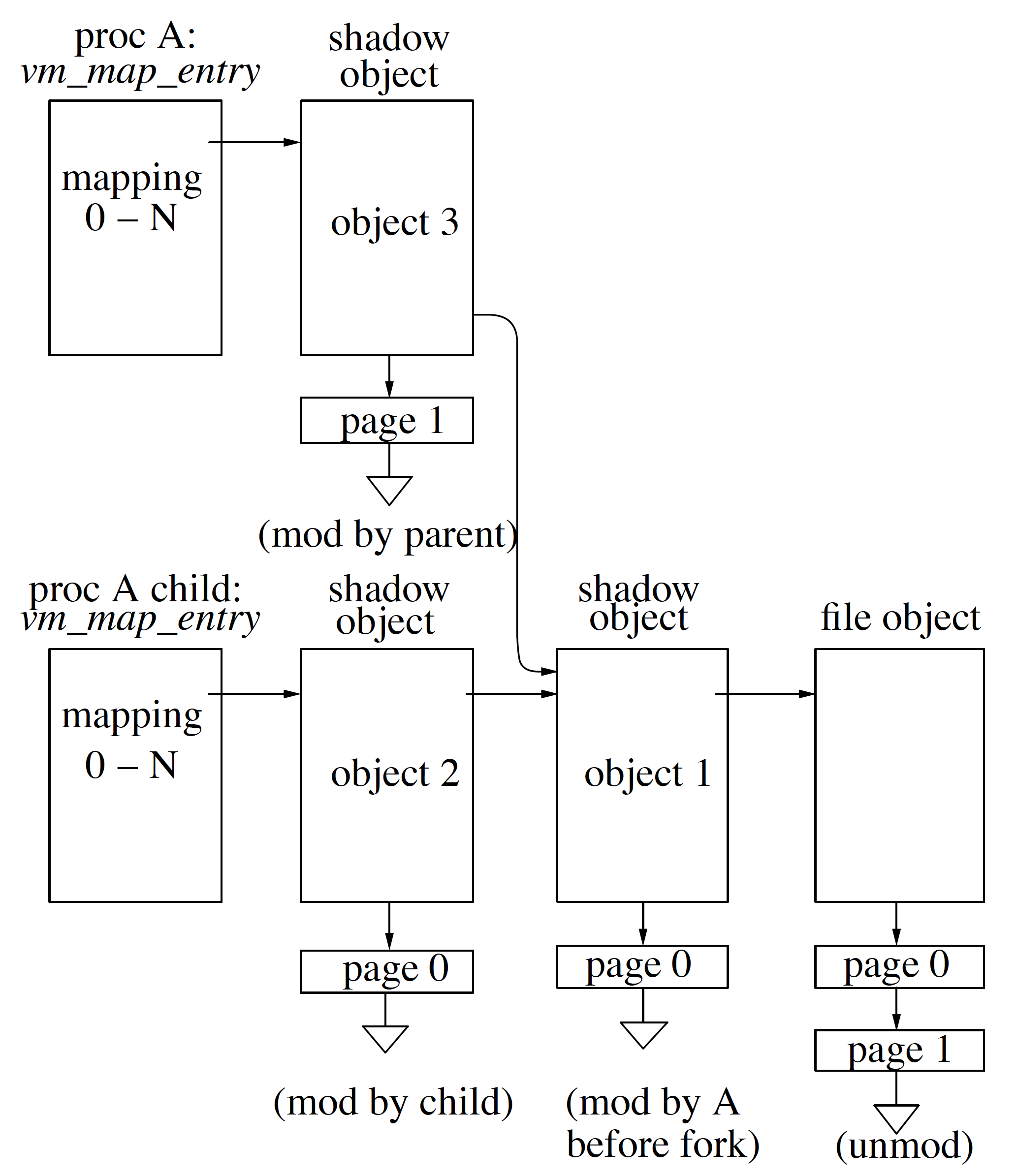

Case 1 Now, let’s take a case when process forks and how shadow objects come into play.

During fork child want exactly the same copy of the parent. Given, we had shadow objects created by parent above we don’t want the child to see those shadow objects. We are going to solve that by using shadow chain objects. In Figure shadowobjectfork, at the top left we have process A vm_map_entry and at bottom we have process A child (from fork) vm_map_entry. Both parent process A and child process of A have to see file object(file object in figure) and pages modified before fork operation. In Figure hadowobjectfork child process A can not modify [page 0 of file object] because that is the original page and also can not modify [page 0 of object 1] because then parent would also see the changes through object 3. So, to solve this we create another copy of [page 0 of file object] and put is as [object 2 of page 0].

In the parent process, page 1 has to be modified, and we have to create a shadow object 3 so that the child does not see the changes. All in all, any changes after fork happened child and parent needs to have their private copy, i.e., shadow objects so that one process does not interfere with another process.

Case 2 Now, let’s consider the case of parent process exits, but the child process is still active. During exiting of parent process from Figure shadowobjectfork, process A vm_map_entry, shadow object 3 and it’s pages goes away. As a result, the pointer from object 3 to object 1 shadow object doesn’t exist anymore too. Now, child process A vm_map_entry points to [object2 \(\rightarrow\) page0] \(\rightarrow\) [object1 \(\rightarrow\) page0] where parent is not referencing shadow object 1 anymore so we can now merge both objects [object2, object1] and also merge the pages hanging to them which is called shadow page collapsing. page 0 exists in both object 2 and object 1 so in this case we throw away the page 0 of object 1 as it is not nearest from child process of A. In case of duplicate pages we keep the page nearest to the child process vm_map_entry and throw away others.

Case 3 In case child process of A have exit before parent process A, we would have [object3, object1] and given none of the pages in [object3, object1] overlaps/duplicate we would have mapping as [object3 \(\rightarrow\) page1] \(\rightarrow\) [object1 \(\rightarrow\) page0].

Case 4 In this case, we have parent process A, child of process A and third process. File object, which is at far right in Figure shadowobjectfork, have shared mapping. The goal of shared mapping is that changes in the file being reflected to all the process. This adds complexity in the system as we have parent, child process, shadow objects which are privately mapped, which leads to ad-hoc mixtures of pages. We have copy object and the purpose is that when we do the private mapping, we get a snapshot of the file at that instance of time. Any changes in base file object pages happen before modifications happen we create a copy of the object and call it copy object. Copy object is placed between the shadow object and file object. Copy object is simply a snapshot in time as before every modification we create a copy object. Copy object concept is specific to FreeBSD system. Copy object is expensive, and since we have another system call read to create snapshots, it does not exist anymore.

Kernel Malloc

Characteristics:

- Kernel uses malloc lot more than userspace

- Can not use the stack for large objects as a result have to use malloc

- Kernel is a resource constraint

- Kernel size is fixed at boot time

- Kernel size can not more than half of the physical memory

- Memory mapping hardware can be directly controlled

- Most allocations are small or size of power of 2

Traditionally, malloc tracks size allocation but adding size information in extra 4 bytes of a specified size for malloc but this bad design as sizes need to be rounded off to the next closest power of 2. For e.g., if given size to malloc is 128 bytes, then 4 bytes added to it for size info so now it has become 132 bytes. Nearest power of 2 is 256 so kernel would try to allocate 256 bytes instead of 128 which is wastage of memory.

Solution We have an array to keep track of one entry per page what size of things are allocated on that page. So, we have fixed size pages for different sizes. This works well for small allocations, but for large allocations, we use zone based allocators.

In Zone based allocator, we create buckets one per data structure type. We would have buckets for vnode, process entry, inodes, and so on. Instead of using malloc() now we use zalloc() which takes data type instead of size.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

void* uma_zalloc(uma_zone_t zone, int flags)

struct uma_zone {

char*uz_name; /* Text name of the zone */

struct mtx*uz_lock; /* Lock for the zone (keg's lock) */

LIST_ENTRY(uma_zone)uz_link; /* List of all zones in keg */

LIST_HEAD(,uma_bucket)uz_full_bucket;/* full buckets */

LIST_HEAD(,uma_bucket)uz_free_bucket;/* Buckets for frees */

LIST_HEAD(,uma_klink)uz_kegs;/* List of kegs. */

struct uma_klinkuz_klink;/* klink for first keg. */

uma_slaballocuz_slab; /* Allocate a slab from the backend. */

uma_ctoruz_ctor; /* Constructor for each allocation */

uma_dtoruz_dtor; /* Destructor */

uma_inituz_init; /* Initializer for each item */

uma_finiuz_fini; /* Discards memory */

u_int64_tuz_allocs; /* Total number of allocations */

u_int64_tuz_frees; /* Total number of frees */

u_int64_tuz_fails; /* Total number of alloc failures */

u_int32_tuz_flags; /* Flags inherited from kegs */

u_int32_tuz_size; /* Size inherited from kegs */

uint16_tuz_fills; /* Outstanding bucket fills */

uint16_tuz_count; /* Highest value ub_ptr can have */

/*

* This HAS to be the last item because we adjust the zone size

* based on NCPU and then allocate the space for the zones.

*/

struct uma_cacheuz_cpu[1];/* Per CPU caches */

};

The benefits of using Zone-based allocation:

- Allocation can happen one after another rather than rounding in case of a power of 2

- It avoid cache line problem i.e., in this model we don’t have data in the same offset across pages

- With allocation initialization needs to happen so for something complex like process entry where initialization has to be done for list heads, locks, mutexes, etc. In this model, we initialize only once and then re-use every time instead of creating and initializing, again and again,

- As memory gets freed in this model it fits the data types only so we need a mechanism where we can reclaim the free memory and can be able to use it freely. In case of freeing up, we need to deregister all the mutexes, locks, etc. i.e., inverse of whatever we did in step 1. Once we do that, then we can free the memory so that it can then be used by zone allocator for other data types.

Page Types

- Wired Pages - These pages can not be taken away by anyone

- Active Pages - In User Process represents pages in use

- Inactive Pages - In User Process represents pages in use but with modified contents

- Cache Pages - In User Process represents valid content but clean(not modified)

- Free Pages - In User Process represents no valid contents and available for immediate use

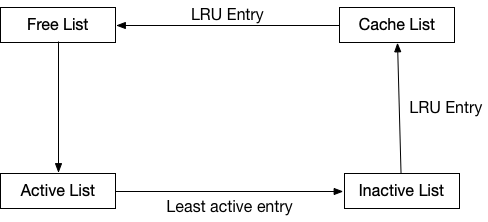

Kernel page daemon tries to keep 0-5% of pages in inactive list, 1-3% of pages in the free list, 3-6% of pages in cache list in the system.

Paging Strategies

To add to Free List:

- Start by removing oldest page to cache list which is LRU list.

- Delete the identity of the page. Identity is usually tied up with vnode or vm_object if it is a page from a file. Freeing up page means is that removing it from the object list.

To add to Cache List:

- Remove the oldest page from the inactive list which is LRU so remove from the front of the list

- We set the scan so that we know we have looked it through and if a page is accessed frequently it can happen it comes again back of the list

- If scan and dirty bit of page are set then we are going to write it and put it on the inactive list. For many files, we delay up to 30 secs to write back the changes and the hope is by second scan cycle it should have written back to the disk. We are delaying the changes to be written to disk due to this procedure instead replying that in the meantime normal course of activities would itself lead to a dirty page to written back to disk and by the time we saw it next we are good to put it to the inactive list

- Otherwise if the page is clean then put it in the cache list

To add to Inactive List:

- Take the oldest page from an active list by using Least Actively Used

- If any executables are referencing the page then we increase the active count and put it back on the list

- If not in use and decrement the active count and if the count is still greater than 0 then we put the page back into the list

- If the active count has reached to zero then we clear the scan flag and move the page to the end of the inactive list

Page Coloring

Failure to do this would lead to significant degradation of system performance. Hardware cache has some size sometimes they are two or three-way SetAssociativeCaches.

The idea of page coloring is to best we can to layout segment of address space so that its layout the pages nicely, i.e., we don’t want to fill the whole cache with same tag bit(SetAssociativeCaches) we want the even distribution of tag bits in the cache so that performance is better.